Rowland Atkinson

The world seems to keep getting more unpredictable, and darker. So many assumptions we may have had, about the conventions of economic and political life, about the extent of corruption, are being unsettled or overturned every day. There are few clear or stable reference points to hold on to. From the perspective of right-populism, this is very much the plan. The sense we have of our current moment is exactly one that Durkheim would have recognised through the lens of his concept of anomie – a sense of drift, senselessness, extreme moral ambiguity and the fading or movement of the codes governing our conduct and goals in life. We can being anomie, finance, and the dark world together in viewing life in a city like London…

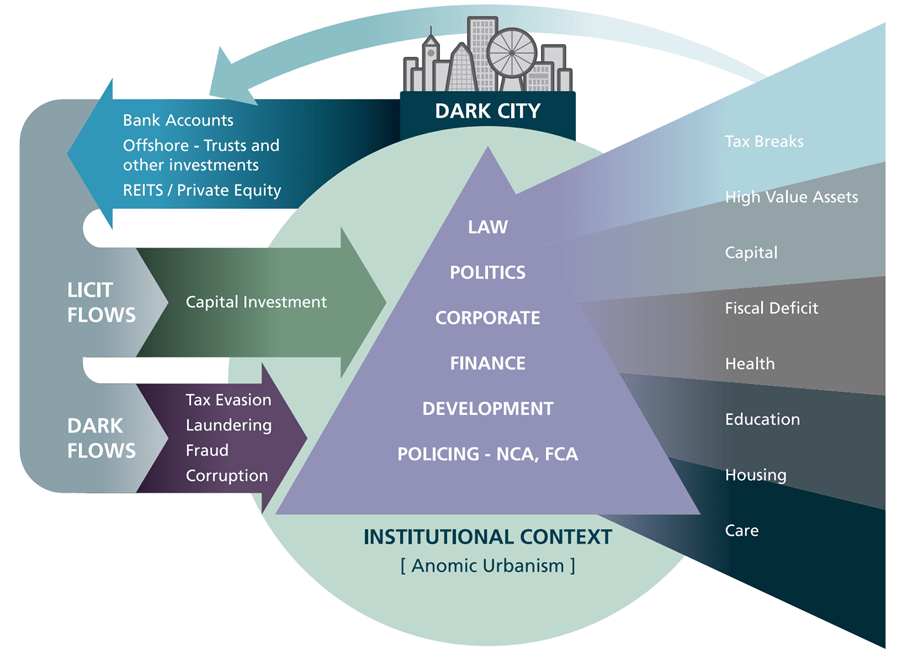

I recently had published an article in the British Journal of Criminology concerning illicit financial flows. I had been writing this piece for a very long time, which tried to summarise the relationship between the illicit finance, laundering, and the way that the city is set-up to adopt illicit as well as conventional capital. I knew that I wanted to help other people to see these processes in some kind of schematic model (see below), and to develop a conceptual framework that would help in the identification of something that might otherwise appear ephemeral or invisible, despite the fact we are all well aware that corruption and financial malpractice are really enormous issues. So this piece tries to get at the scale of this stuff, looking at many of the empirical assessments out there, and also to develop a new concept of the dark city, in which conventional capital flows and illicit finance are beamed together through the prismatic, morally negotiable, world of finance, law, property development, and politics.

But trying to write this piece, this week (the second week of February 2026), the world again looks different, just that bit bleaker and just ever so slightly more….anomic. But let’s turn to the piece itself.

1. An economy of light and dark, choose your side….

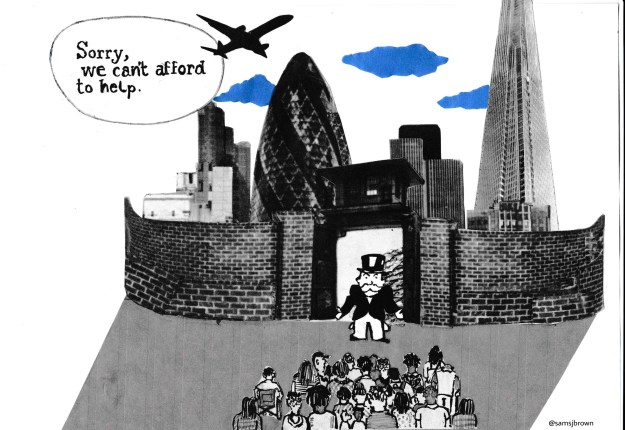

A question for our times, not just for Londoners, is who the city is for. If nothing else finance already feels as though it has robbed its citizens of prospects for a good life. In addition we can also ask, what happens to a city that is a conduit for good and bad global capital? In case you didn’t already know it, the city is simply one of the worst for facilitating dark money flows, and that means enabling criminality, violence, torture, organised criminality and political corruption elsewhere, but some of these things here too.

The limits of a finance-based economy are one thing, and have long exercised economists, but this finance stuff, that’s a whole other ball game. As daily revelations by investigative journalists are showing, the rot is deeper and worse than many had feared. So we might begin by simply listing the brief details of some case that I think you are unlikely to have heard about, but which speak of the kind of culture of the institutions in charge not only of the everyday capitalist economy, but who are also involved (both intentionally and not) in its darkside (feel free to skip ahead here!):

- 45,000 UK properties worth an estimated £190bn are owned through offshore structures where the true beneficial owner cannot be identified. London accounts for around £107bn of the estimated hidden property value. https://thenegotiator.co.uk/news/regulation-law-news/foreign-owners-hiding-190bn-of-uk-property-claims-tax-think-tank/

- Members of Azerbaijan’s Aliyev and Pashayev families directly or through associates spent over £400 million on UK property between 2006 and 2017. A report by John Heathershaw and colleagues lists this case among 97 other cases of former Soviet PEPs purchasing in London in relation to £2bn worth of property The UK’s kleptocracy problem | Chatham House – International Affairs Think Tank

- In 2023 Private Eye reported that £350m property alone in the development One Hyde Park had been purchased by Politically Exposed Persons using 45 shell companies, of these 8 gave the names of trustees, but not beneficial owners, and another 18 concealed ownership via the use of trusts.

- The company SmartSearch revealed that money laundering is significantly inflating property prices across the UK, making homeownership increasingly unaffordable. Their analysis suggested that illicit money entering the housing market has pushed up average property prices by £3,000 across the country, and by more than £11,000 in prime areas (as much as 20). Since 2016, over £11bn in suspicious wealth has flowed into UK real estate, with more than half linked to shell companies registered in British Overseas Territories https://fintech.global/2025/08/28/estate-agents-warned-on-aml-failings-in-uk-housing-market/

- 87,000 properties are now owned by anonymous firms based in tax havens, collectively valued at more than £100bn, 40% of these are in London alone https://fintech.global/2025/08/28/estate-agents-warned-on-aml-failings-in-uk-housing-market/

- £4m were paid in legal fees to UK lawyers acting for sanctioned Russian individuals in the four months from October 2023 according to the Office of Financial Sanctions Implementation (Private Eye, 10 May 2024)

- In 2024 Transparency International revealed that 78,735 donations worth £1.19bn had been reported to the Electoral Commission between 2001 and 2024. £115m came from unknown or “questionable” sources – equivalent to almost £1 in £10 donated to parties from private sources. More than two-thirds – £81.6m – went to the Conservatives, £48m to politicians and parties by donors alleged or proven to have bought privileged access, influence or honours; £42m came from donors alleged or proven to have been involved in corruption, fraud or money laundering. Revealed: UK politics infiltrated by ‘dark money’ with 10% of donations from dubious sources | Party funding | The Guardian

- In 2025 the Reform party held a fundraiser in Las Vegas, announcing that the party would accept donations in Bitcoin and would commit to a bill on “Crypto Assets and Digital Finance Bill”. Reform UK to accept Bitcoin donations, says Farage – BBC News

2. The Dark City

One of the key contributions of the article is trying to help the reader to see and to understand the kind of systemic architecture and interplay of key actors in the urban economy of London. This economy is distinctively constituted of key actors and institutions who are implicated in both illicit and formal financial flows. An immediate concern perhaps might be with key actors working in finance itself, but this sector is only part of a larger system that takes in other actors and institutions – notably in law, property development, the political world, and wealth management.

Cities with extensive financial architectures—such as London, New York, Dubai, and Hong Kong—create conditions that actively support the processing of illicit capital (or “dark money”). These urban centres act as both facilitators for moving criminal funds and destinations where such capital is absorbed into assets like real estate. But you know that already!

The next step in the argument is to show that “dark city” is a setting where the institutional culture and political economy favour (due to the anomic conditions that prevail) the processing of illicit and conventional capital. The cost of this is social investment, which suffers directly because of the reduced levels of tax that are collected, while the finance sector is lionised.

3. Anomie and Urban Political Economy

Two primary theoretical lenses can be used to think through these arrangements:

- Institutional Anomie Theory (IAT): This theory views economic crime as socially embedded in environments characterized by “normative indeterminacy” or a lack of clear social rules. In dark cities, a market-society ideology encourages aggressive competition and the innovative breaking of rules to achieve material success.

- Critical Urban Political Economy: Finance capitalism is intertwined with city and national-level political administration. The dominance of the finance sector has lead to a finance curse. In this kind of context the needs of the economic elite displace other industries and increase the social cost of living for the general population.

4. Sources, Destinations, and Enablers of “Dark Money”

Illicit capital flows originate from four primary sources: tax evasion, aggressive tax avoidance, corruption by “politically exposed persons” (PEPs), and the proceeds of serious crime. This money is funnelled into three main destinations:

i. Offshore Finance: Concealing identity and allowing money to later flow into licit investments.

ii. Assets: Particularly high-end real estate, which offers both public respectability and a “safety deposit box” to store value.

iii. Everyday Spending: Integrating funds into the formal economy through the purchase of goods and services.

Of course, the notable thing here is that such a system relies on a vast network of enablers, including lawyers, bankers, estate agents, wealth managers, and tax advisers. These professionals help the wealthy and corrupt navigate complex regulations and use anonymous trusts or shell companies to avoid public scrutiny. This is being shown time and again by journalists and NGOs.

5. Life in a dark city

Really the point of all of this preamble is to lead us to the central point – the kinds of social harms that a dark city will produce. I identify three major areas of harm resulting from the dark city configuration:

i. The De-Policing of Economic Crime – While economic crime costs the UK an estimated £350 billion annually, the budget for fighting it is only 0.042% of GDP. The National Crime Agency (NCA) has faced budget cuts, and regulatory bodies like the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) have made very few successful prosecutions for financial crimes. This “network neutralisation” occurs because the benefits of dark money to the formal economy encourage political passivity.

ii. Urban Disinvestment and the Housing Crisis – Illicit capital flows drive up house prices and encourage the construction of “prime” properties that often sit empty as investments. This contributes to:

Loss of Social Housing: Over 70 public housing estates in London have been demolished to make way for private developments.

Increased Poverty: 28% of Londoners now live in poverty, and rough sleeping has reached critical levels, with 9,000 people sleeping rough nightly in the city.

Community Disruption: The focus on high-end international investment thins social infrastructure and displaces long-term residents.

iii. Ideological Capture – There is a triumph of ideology over evidence, where political focus is often directed at welfare fraud, for example, despite the fact that the UK loses nine times more money to tax fraud. The finance sector is paraded as a core economic generator, leading actors within the system to accept the presence of illicit capital as a necessary moral shadow-play for global finance.

Conclusion

Theory is important to guiding the actions of policymakers and communities touched by the costs of criminal capital. One of the things that the dark city model tries to achieve is to help us to visualise the architecture of something as complex as the urban economy, its relationship to illicit financial flows, and the kinds of outputs that this generates for everyday urban life.

An important point to be made is that this is not simply a question of weak governance. As many commentators and NGOs have pointed out, the structure of the system continues to work in ways that advantage criminals, their intermediaries, and all of the shades of grey that exist between these institutions and actors. The more we look, the more like the Wild West cities like London look. The role of government, major financial institutions, reputable legal teams are shown to act in concert with, to second guess, or to simply accept criminal capital – bad money is good for business and shapes the kinds of norms into which it often flows.

Dark cities can be used as a concept to apply to cities in general where the pursuit of global financial dominance, or simply striving to win, creates an environment where illicit and legitimate capital become indistinguishable. While this brings massive wealth to a narrow class of enablers and institutions, the resulting social harms—including depleted state capacity, a massive housing crisis, and the erosion of regulatory standards—are borne by the wider urban population.

Rowland Atkinson, 12th February 2026

Dark Cities can be freely downloaded HERE